by Ashley Woodward

Popular culture has already had more than its fair share of misrepresentations of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) and his ideas, from the comic book superhero Superman to the‘Nietzscheans’ – a malevolent alien race who care only about power – in Andromeda,another sci-fi series by Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry. Season 3 of the television series The Sinner (USA Network 2020) unfortunately repeats this common tendency to sell Nietzsche short.

The story (spoiler warning) focuses on Jamie Burns, a schoolteacher whose existential crisis leads him to murder. In his university days (to which we get frequent flashbacks) he had studied philosophy and fallen under the influence of a charismatic but dangerous fellow pupil, Nick Hass. Hass embraces a terrifyingly literal understanding of Nietzsche’s idea that one should ‘live dangerously’: involving, for example, jumping off bridges. In a world in which there are no objective values, he believes, people conform to accepted norms of belief and behaviour to protect them from this truth. The world is in fact chaos and randomness, and the most appropriate way to behave is also random. Burns and Hass use an origami fortune teller to decide their actions (in response to questions such as Should I jump off the bridge? Should I kill someone? Etc.). University ends and the friends drift apart. But married, holding down a respectable job, and approaching middle age, Burns starts to realise that he feelsnothing in this life of safe conformity, and contacts his old friend. This leads him down a path involving increasingly antisocial and out of control behaviour, ending with a series of murders.

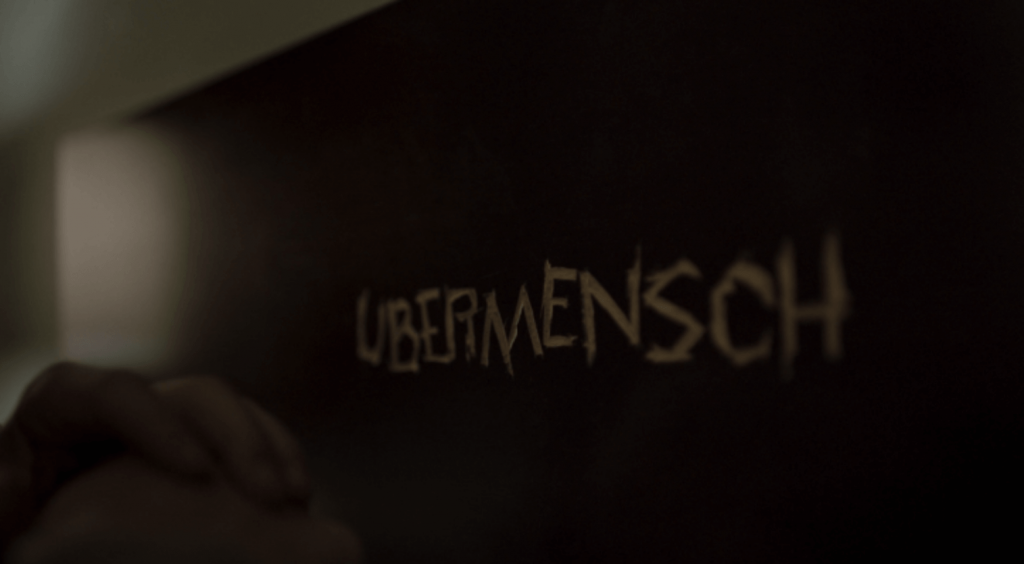

Nietzsche is frequently referenced throughout the series as Burns and Haas’ primary philosophical inspiration. There is a brief explanation of some of his ideas by a philosophy professor, and a scene in which the young Burns reads some passages from a Nietzsche book while Haas carves the word Übermensch (‘superman’) into his wooden bedhead (so he ‘won’t forget it’). It’s true that murder is an important theme of a number of writers branded existentialist (see for example Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, or Camus’ The Rebel). This makes some sense, for it’s a limit case for the idea of objective moral order, of right and wrong (if anything is really immoral, then surely it’s murder). But murder was never a theme of much interest to Nietzsche. Rather, the link was made by a later historical event.

In 1924, two University of Chicago students, Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, murdered Bobby Franks, a 14 year old boy. Leopold, the older and more dominant of the pair, was influenced by a particular interpretation of Nietzsche’s idea of the Übermensch. He wrote in his diary: ‘A superman … is, on account of certain superior qualities inherent in him, exempted from the ordinary laws which govern men. He is not liable for anything he may do.’ The crime was committed as an act designed to demonstrate the boys’ supposed superiority by transcending customary morality. They were caught and convicted, and the event was described in the press as ‘the crime of the century.’ A number of fictional works have been based on this case – most notably, Hitchcock’s film Rope (1948) – and there is clearly more than a little inspiration taken from it in season 3 of The Sinner.

Understanding Nietzsche’s philosophy as a justification for murder, however, is a fundamental misunderstanding. This was clearly seen by Bernard Shaw, whose ‘Nietzschean’ character Jack Tanner, in the play Man and Superman (1903), explains to his critic: ‘you confuse construction and destruction with creation and murder. They’re quite different: I adore creation and abhor murder.’ The Sinner’s anti-hero Burns actively transgresses social norms for the sake of ‘staring into the abyss,’ of facing the ‘truth’ of the objective meaninglessness of existence. Murder is presented as the ultimate transgression which will reveal the ultimate truth. But Burns continues in his murders, and behaves erratically, tormented by his existential and moral anguish. He is a mess of conflicting drives and inclinations, unable to find any meaningful course of action.

The aim of Nietzsche’s philosophy is quite the contrary: to choose a clear purpose, and to create meaning in the world in accord with it. This requires the strength to unify one’s diverse desires and drives without relying on the external constraints of social custom. Such habits and customs should be actively destroyed in order to create the conditions for a more meaningful and life-affirmative existence. Shaw again understood this: Tanner ‘found [his desires] a mob of appetites and organised them into an army of purposes and principles.’ He describes his subsequent existential development: ‘The moral passion has taken my destructiveness in hand and directed it to moral ends. I have become a reformer, and, like all reformers, an iconoclast. […] I shatter creeds and demolish idols.’ Nietzsche’s destruction was directed against ideas; his entreaty to ‘live dangerously’ refers to the courage to have original thoughts, not to risk one’s life haphazardly or take the lives of others gratuitously. At his most ethically and politically questionable, Nietzsche suggests that the lives of ‘the herd’ might be sacrificed for the higher purposes of the supermen. But The Sinner’s character Burns is a very long way indeed from having any such purpose, and so even by these standards, from being anything like a Nietzschean Übermensch (or even a Nietzschean). In many respects, he is exactly the opposite: he falls into the abyss of meaninglessness and remains there, floundering about committing purposeless acts. His social transgressions are never conceptually or existentially interesting, ranging from the utterly banal (staying out late drinking) to the obviously abhorent (senseless murder).

None of this, of course, speaks against the quality of The Sinner season 3 as entertainment. Like the previous seasons of the series, it is a well-made drama which often makes for compelling viewing. As suggesting an interpretation of Nietzsche, however – it must be said bluntly – it is exasperatingly stupid. Those of us who are better philosophically informed can only regret that, after seventy years of scholarly work on Nietzsche, which has long since saved him from the Nazi taint, these kinds of popular misrepresentations continue to be propagated.

About the Author

Ashley is Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of Dundee (UK).