by Dominic Smith

Two transitional moments in Spielberg’s Jaws demand special attention.

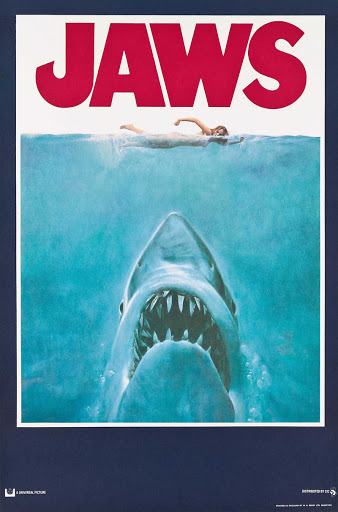

The first is when Richard Dreyfuss turns up as oceanographer Matt Hooper. In a film full of strong performances, he steals the show (opinion will be split on whether Robert Shaw does this better). The second is when we properly get to see the shark. This is the film’s big ‘anxiety to fear‘ set piece. Anxiety at quite what the watery monster will look like has been building from the start, and has been supplemented by glimpses. Now, two thirds of the way through the film, it is going to fasten onto a tangible object.

But whereas Dreyfuss’ appearance increases Jaws’ sense of pathos considerably, the shark’s appearance is pure bathos. Granted, there is a brief shudder when a chum-chucking Roy Scheider first looks it in the eye, and it helps deliver the film’s iconic line in the process (‘we’re going to need a bigger boat’). But consider the scene immediately after: the shark ‘swims’ alongside the boat, with Shaw, Scheider and Dreyfuss all straining for a proper look. This may have been one of the film’s most technically daring and expensive shots. In terms of that anxiety to fear transition, however, it misfires badly.

The point here is not a snide anachronistic one restricted to that poor old steel/polyurethane shark. I am not saying: ‘pity any fools suckered by THAT in a 1970s cinema’.

The point is broader: this scene could only misfire because of a general contradiction affecting the transition from anxiety to fear.

This transition is something that must be done in most movies in the horror/thriller/suspense genres. But it is also something that ought not to be done. It must be done because the film has to end somewhere, and usually has to show the object of fear. It ought not to be done because it is rarely, if ever, satisfying.

This results in a dilemma for filmmakers: either build anxiety to an extreme point, or find a way to make the object of fear really scary. It is a very difficult thing to do both, and each of the successful exceptions to this rule (of which there are many) will have to do it in more or less signature ways, because scariness tends to decrease with predictability.

One way of pulling off the ‘really scary’ move is to go through uncanny valley: by making the object of fear move/appear/behave in an unsettling way, for instance (think of the first Ring film, where the dead girl crawling from the TV is played by an adult male). Jaws, with its rigid nuclear submarine of a shark, does not manage this well.

What Jaws does very well is the other move: before we see the shark, anxiety is built to a point where the shark becomes literally elemental. Until the shark is seen in Jaws, it is not one object among others in the ocean: it is the ocean (nay, water) itself.

Where am I going with this? Well, here it is, this essay’s very own ‘anxiety to fear’ set piece, and apologies if it appears jarring or crass….

The recent COVID-19 crisis is going to demand that every one of us negotiates something comparable to the ‘anxiety to fear’ dilemma that filmmakers find so difficult. And it is going to require each of us to do it not just once in a two-hour feature, but again and again, until new ways of coping become habitual and familiar.

If this sounds like a living hell, bear with me….

Anxiety, as philosophers like Kierkegaard and Heidegger knew well, is ontological. This means it relates to being in general, and the conditions under which literally everything in the world shows up. When one feels anxious, one lacks a tangible object to be anxious at. Instead, what one is properly anxious at is the lack of a tangible object, and this is what manifests itself in anxiety’s general sense of vigilance/uneasiness at not being ‘at home’ in the world.

Now consider how literally everything is showing up to you right now: from the irregularity of the bin collections, to the (pleasant but eerie) sounds of the birds, to the text message sent 10 minutes ago that a loved one has not yet replied to, to that elderly couple coming towards you on the pavement that you intend to ‘socially distance’, to that empty shelf in the supermarket…. If any of these examples resonate, you are anxious. You are far from alone (and, if the examples don’t resonate, my hope is that you are from the – near – future, and that they are snapshots of a world that passed quickly, in favour of a better one).

Everything and nothing can be the ‘object’ of anxiety, because nothing is its proper object (anxiety is a creeping sense of nothingness at the heart of things, to put it in a very Jean-Paul Sartre way). In Jaws, this is how the shark becomes the ocean.

Fear is different. It is epistemological. This is to say that it relates to knowledge and its objects. With fear, one always has objects that one can recognise, localise, and orient oneself towards/away from.

Consider that iconic phrase: ‘you’re going to need a bigger boat’. This implies a very basic and familiar sort of knowledge: of relative size. This might seem like a very trivial thing to note, but that is precisely the point: it relates to a thing, and it is the kind of thing that occurs immediately and implicitly. Up to this point, Scheider’s character has been chain-smoking and chucking chum into the briny blue, and we, the viewers, have been anxiously wondering quite what lurks within it. Now we all know something.

Consider also the scene where the shark pulls alongside the boat: Dreyfuss’ character says ‘it’s a twenty footer’; Shaw says ‘twenty five’. They are building on Scheider’s knowledge. They are sizing up the object of fear, with us along for the ride.

Films are cognitively enriching because they provide us with a means of orienting knowledge dynamics like this, and of reflecting on how they work. Pandemics are massively disorienting in this respect, although I can’t claim to have known it until very recently. This is because they short-circuit our expectations about how knowledge dynamics work (well, at least this one did). Usually, we watch films to get concentrated shots of particular plot dynamics, like the anxiety to fear transition. In this pandemic, we are all at sea.

It is tempting to conclude that we have become characters in a very unfamiliar film. But we are not in a film, and that is the main point I’d like to make.

First and foremost, there are those who have ‘seen the shark’ of COVID-19: those who have been seriously ill with it, those who have died from it, those who treat and care for those affected, and those who are studying it and trying to ‘size it up’. In trying to make sense of such circumstances, analogies with films wholly break apart: they may be of some use and/or consolation, but the chances are that they will simply show up as cheap, facile, and thoughtless (it is tempting to say that they run aground on terra incognita, but that would remain within the tendency).

There are, however, other ways in which we (i.e. all of us) are not in a film. Whereas Dreyfuss et al had to hunt the shark in Jaws in its element, we and our behaviours are, properly speaking, the element of COVID-19. Guns, cages, and harpoons will not help us here, and metaphors that frame things like this will simply risk turning crude instruments of thought against ourselves. Likewise, metaphors that make this into a ‘war’ against a conventionally recognisable object will only take us so far.

Spielberg’s intention had been for more of the shark to be seen earlier in Jaws. In fact, three models of the shark were used (collectively named ‘Bruce’), and there was a litany of problems trying to float any of them. That the team behind the film managed to show us anything at all ought to be recognised as an impressive cinematic feat.

Unlike Spielberg, we do not have to build floatable polyurethane sharks. We have to do something much more subtle, long term, and, one hopes, manageable: we have to go through that anxiety to fear transition again and again, until it produces new forms of knowledge and new ways of coping that become unconscious and familiar. This will not be heroic or pyrotechnic, and won’t win any Oscars. But it will be liveable, and, done well, it might even let us flourish.

It may, for instance, involve developing a sense of ‘social distancing’, not as distance from the social, but as distancing that is social (think, perhaps, of all those ‘hellos’ and smiles you’ve been emitting to strangers on the street recently…. Or think of some volunteering or creative work you might have been doing…. Or think of little drawings you might have been doing with your kids…. Or of any number of calls or texts…).

It may also involve channelling anxieties about the future towards better ends: towards a world where carbon emissions are radically reduced as a matter of course, for instance, and not because a cataclysm shows up as an emergency brake on bizarre forms of (over) industriousness that the whole world has been suffering from for quite some time.

It will also involve facing up to lasting scars. As a very unscientific measure, consider the forms of galeophobia (fear of sharks) and aquaphobia (fear of water) Jaws heightened: from fear of swimming at the beach or pool, to fear of the open sea, to fear of the bath, to, we might luridly speculate, fear of baring one’s backside to toilet water (a kind of regression to potty-training/shark phobic double-whammy there). Consider also the kinds of irrational hatred/persecution of sharks that followed Jaws. If a film can do that, what can a pandemic do?

Seeing the shark in Jaws was a bad thing – a scuttling for a sense of anxiety that had been riveting (and that will return in the film, by the way, as in the scene when the shark has the good grace not to be seen, but heard, thudding against the hull of the Orca, a boat that, as we know, isn’t big enough….)

When we approach this film as a little machine for thinking, however, that sense of anti-climax shows up in a different light. The fact is that no one wants the anxieties provoked by COVID-19 to go on forever. There are at least two things we want instead: 1.) for the transition from anxiety to fear to be as anticlimactic as it can possibly be, for as many as possible; 2.) for a different kind of transition to emerge and steal the show.

In contrast to the anxiety to fear transition, the show stealer would be an anxiety to flourishing transition: one that would take up all those anxious energies stirred up by this event, and that would invest them in consolidated thoughts, actions and habits for a better world, chock full of stronger and more sustainable ways of living together.

You might call the first desire the ‘polyurethane shark effect’.

You might call the second the ‘Matt Hooper effect’. After all, he was a hyperactive idealist, content to play an educated supporting role, not that of the hero, even once he’d seen the shark.