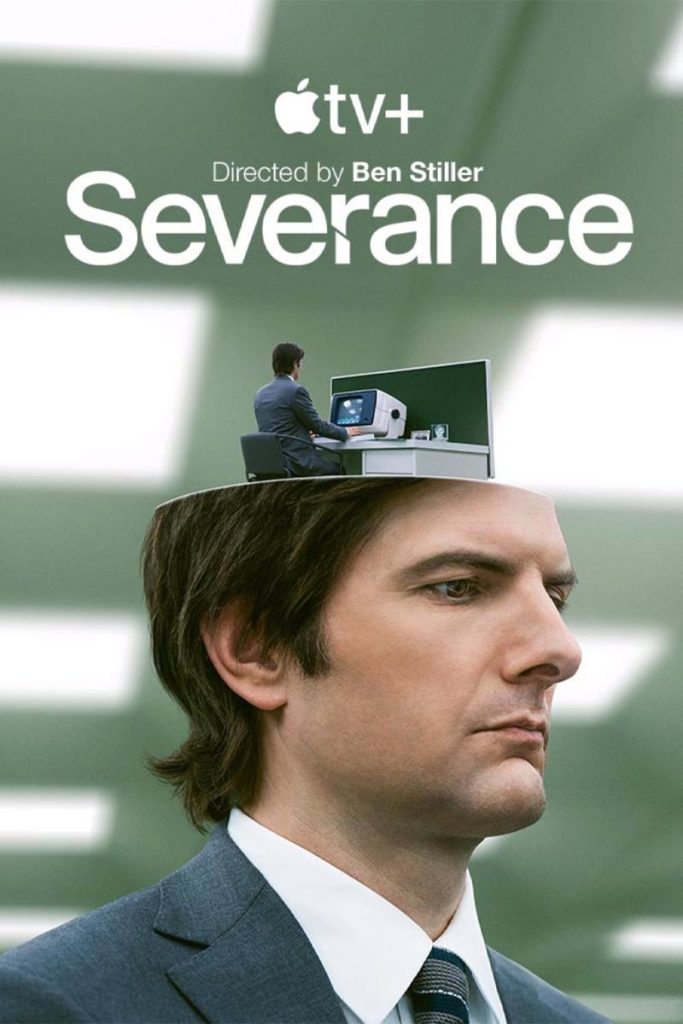

Forget the big hits like Stranger Things, Squid Game or Bridgerton. You know, these shows that break records, generate trends on Tik Tok, and are responsible each year for a tons of new Halloween costumes. Severance, directed by Ben Stiller and released on Apple TV+, is none of that, yet it is a hit, praised for its excellent cast, its audacious storytelling, and its acute sense of mystery. It did not come with a bang, but it gained more viewers every week and silently reached a cult status.

Over nine episodes, Severance follows a series of characters who go through a medical procedure to have their private memory separated from their work memory, hence resulting into two different personas: one that exists only outside the office, the other only inside. The advantage, or so it seems, is that each version of themselves can fully focus on and appreciate their time spent in or out of the office, for the simple reason that these two realities are guaranteed by the firm not to overlap. Of course, there is a twist. Critique of the work-life balance concept, of capitalism of surveillance or the work-corporate culture, Severance is probably all that at once, and more. It brings Marx’s theory of work to the test.

Marx is known for viewing work as what gives meaning to human existence. Far from the grim assertions about work being a burden to humanity, a stone to be pushed each day to the top of the hill, Marx contends that it is a productive activity essential to our self-realization. It is creative, fulfilling, and rewarding – but only if there is a continuity between production and consumption. In other words, my labouring has the capacity to become meaningful to me, and participate to my flourishing, if I can access, use, own, enjoy, care, and therefore appropriate the results of my own activity. The hardship of my labour makes sense to me and has a purpose, because I fully benefit from it. Whenever a separation between production and consumption occurs, so that I can produce but not consume (I work ten hours a day for a wage that only allows me to buy commodities worth no more than three hours of labour, for example), or I can consume but not produce (I work for a wage that allows me to entertain myself through various means, cinema, concert, and so on, while being incapable of producing these means for myself), I become alienated from my work. I am dispossessed of a part of my humanity. I am exploited.

Severance is a story of work alienation. Like Marx, it focuses on the idea of separation, the so-called ‘severance’ program, and like Marx, it suggests that to be cut off from your productive activity slowly deprives you of your humanity — the latter rendered evident in the show by the main character’s failure to pursue a flourishing life both inside and outside the walls of company. But while Marx considered alienation to be the fault of capitalism, only desirable for those who own and accumulate capital at the expense of a powerless and repeatedly cheated working class, Severance questions the complicity of the worker, who agreed to the procedure for convenience and comfort.

Yes, alienation may be desirable, even from the other side of the class struggle.

For a start, the ‘severance’ deal sounds attractive. Imagine being able to fully enjoy your mornings and evenings with no recollection of your very boring, unsatisfying, and exhausting, ten-hour day at the desk. You get into an elevator to reach your office and the next second, you are back on the ground floor, ready to leave. A full day of work just happened, but you don’t remember, and don’t have to, because this is none of your concern, none of your business. Off you go, enjoying a pint of beer, a diner with friends, an evening at the cinema. Outside the building, your boss does not exist, your job means nothing. Who would not dream of that at a time where cases of burnout are skyrocketing and where the infamous Sunday blues, an anticipatory anxiety about the impending Monday, is robbing you of the joys of your weekend? This is exactly what draws the characters to the severance program offered by the biotech company Lumon.

But every gift comes with a cost: while a version of you can enjoy a life without worrying for a single minute about her job, another version of you is trapped for ever at the office, with no knowledge of what it is like to be outside. Here starts the dystopia about an existence forever bound to your professional self, your colleagues, your daily tasks, and of course, the demands of your boss who considers that a full devotion to the company isn’t too much to ask since there is a version of you that lives with no responsibility whatsoever towards that same company.

The distressing part of Severance is that the worker is not cheated; it is all done with her consent. When one of the newcomers has enough of this lifestyle, confined in a very 80’s office space, obliged to complete futile tasks and repeat those indefinitely, she has the possibility to resign. Knowing that, she presents her concerns to her outside self. However, the outside self firmly declines. The outside self has signed and agreed to the terms and conditions with full awareness of what it is like to be inside and has chosen not to care about this other self. The price for her peace of mind comes with one part of herself being sold to the biotech company.

Severance is not just another story about work alienation. It does not just explore Marx’s theory of labour under capitalism as soulless exploitation. It is a story of a Faustian bargain. The grim observation made by the show is that one can consent to their fundamental rights being abused due to their failure to recognize the abuse as such.

To understand the disturbing relevance of Severance today, it suffices to take look at the Amnesty International Report published in 2019 regarding the business model of the 5 biggest tech companies: Microsoft, Facebook, Apple, Google, and Amazon.

These five giants set the terms for the quasi-totality of human interactions in the digital sphere; terms to which we agree on a daily basis. Every website we visit, every application we open, every computer we use, will eventually ask us to tick a box as a trace of our consent. In letting us enjoy their services, these platforms collect “extensive data on what we search; where we go; who we talk to; what we say; what we read; and, through the analysis made possible by computing advances, have the power to infer what our moods, ethnicities, sexual orientation, political opinions, and vulnerabilities may be. Some of these categories are made available to others for the purpose of targeting internet users with advertisements and other information”.

The report observes that the business model of these companies works like a twisted bargain, for if the services they offer are based on the enjoyment of human rights, they threaten these same human rights — our right to privacy for a start, of self-determination, but also freedom of thought, opinion, and expression — with the user’s approval. The reason this business model is allowed to grow, other than the government’s failure to address the political and ethical issues raised by the internet, is because people fail to understand their rights online, how data work, and how value can be extracted and monetized from them. After all, “does it truly matter that Facebook knows that I travel monthly with EasyJet and advertise flight tickets to me if it means I don’t need to waste time browsing for interesting prices?” one might wonder. For sure, this is quite convenient.

The report reminds us that the internet is a valuable invention that has become central to how we communicate, learn, participate in the economy, and organise socially and politically; it is easy, smooth, and efficient. But the other reality is that our online activities generate revenue that enrich the companies on the basis of a simple separation between our online and off-line persona and a false perception of their political relevance. The report stresses that the frequent spying activities conducted by Facebook and Google on their users would have never been tolerated by the public if these were performed by governments. If this shows anything, it is that we struggle to understand the true magnitude of power exerted by these companies on our ability to think, to choose and to express ourselves both online and offline.

Going back to Marx’s theory of alienation and Severance, this means that it is like we have agreed to be separated and in doing so, we have become estranged to a part of us that is producing value for the profit of a giant tech company.

Like in Severance, we sign off our digital persona to the tech companies, convinced that what truly matters are the interests of our off-line persona.

Like in Severance, we minimize the impact the bargain has on our other self, forgetting that this other remains our self and that we do have equal rights to them and the value they produce.

Like in Severance, we have split ourselves for the needs of two different realities, or spheres of existence, believing that one cannot overlap with the other.

Author:

Dr. Amélie Berger-Soraruff

References:

Amnesty International, Surveillance Giants: How the Business Model of Google and Facebook Threatens Human Rights (London: Amnesty International, 2019), available at: https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/POL3014042019ENGLISH.PDF.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels, Marx and Engels Collected Works, (New York and London: International Publishers. 1975).